This piece originally appeared on the School of Humanities blog, “Reflection and Choice”

By Dr. Chris Hammons, Professor of Government and Director of the Morris Family Center for Law & Liberty

I love teaching students about the American Founding. I like the philosophical debates over the nature of liberty and necessity of government. I like the use of pen and paper as weapons in a war of ideas. I like the manner in which gentlemen addressed one another, even when they disagreed. I appreciate the emphasis on honor and duty exhibited by statesmen and soldiers. Everything about early America appeals to me – the architecture, the long coats, the tricorn hats – even the weather. I always think of late-18th century America as perpetually stuck in autumn, with air that is cool and crisp, and a sun that always shines. I know that isn’t true, but that’s how I envision it.

It’s easy to romanticize the American Founding as a period of unbridled optimism, achievement and glory. The truth is that the period right after the Revolution, before the Constitution was drafted, was a dangerous time for the United States. For about ten years, after the battle for independence was won, the fight for freedom gave way to the darker side of human nature. Had less enlightened forces prevailed, the American Experiment would have failed before it began.

Like Greece and Rome before her, the infant United States almost fell victim to a military cabal bent on using force of arms to take charge of the government. The incident involved soldiers who were angry about not receiving their pay. During the Revolution, citizen soldiers were often promised payment for their service only to be told later that no funds were available. In some instances, soldiers who had served five or six years in the fight for American Independence were still not paid when the war was won.

In 1783, some of our Founding Fathers, including Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris, concocted a scheme to use the unpaid, angry Army as a means of pressing Congress to assume the power to collect taxes from the new American states. The Army was enlisted to march to the capital (then Philadelphia) and threaten to seize power by force if necessary in order to receive their back pay. Since Congress was broke, Hamilton and Morris wagered that the legislature would be forced to adopt strong taxation powers as means of quickly raising funds to buy off the besieging Army. The plot, conducted in secret, was designed to use the Army as a means of shaping public policy. In essence, what Hamilton, Morris and their confederates planned was a return of the principle of military involvement in government affairs that characterized much of human history, particularly the histories of Greece and Rome. Had the coup been successful and Congress subdued, American democracy would have been crushed before it began, and our subsequent history might look much different.

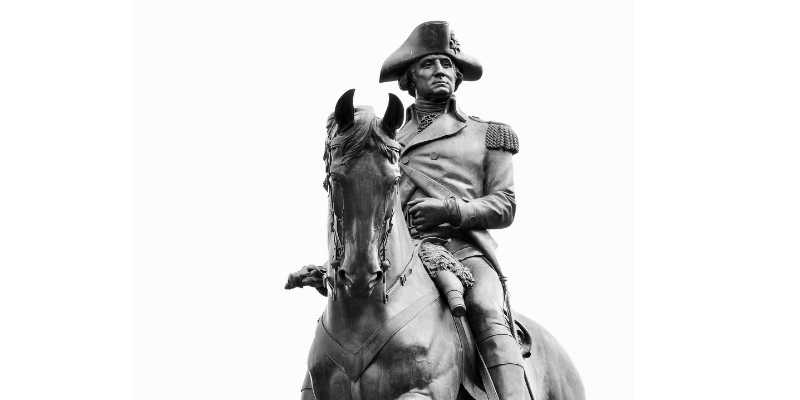

One thing, or to be more precise, one man, saved the infant nation. George Washington was recruited to lead the military coup by Alexander Hamilton. Washington received Hamilton’s letter to lead the charge, rejected the idea outright, and immediately called an impromptu meeting of his military officers on March 15, 1783. The officers (unaware of his response to Hamilton) suspected that Washington was supportive of the plot and would announce his

intention to ride at the head of the Army to collect the treasure that was rightfully theirs. He would, in essence, pull a Julius Caesar.

Instead, Washington spoke gently but firmly to his fellow officers about duty, honor and love of country. And then, in the most well-staged use of theatrical flair to ever save a nation, Washington asked to read from a letter he had received from Congress. In doing so, he pulled from his breast pocket his new reading glasses, which he had just received. In fumbling to put them on, he asked his men to forgive his clumsiness, as he had “grown both old and blind in the service of my country.”

The guilt and shame of seeing Washington – the hero of the Revolution, who had sacrificed so much for others – in this humbling and human condition, shamed the officers into reconsidering their motives and plans. According to witnesses, men openly cried and asked Washington for forgiveness. The coup that could have been, never was. The republic was saved.

The future of American democracy wasn’t guaranteed by the rhetoric of the Revolution or the victory at Yorktown. The United States could have gone the way of Greece or Rome – systems based more on power and might than principles of liberty and equality. Our nation is an experiment – an experiment to see if men really can govern themselves by “reflection and choice, rather than accident or force.” How this experiment ends is largely up to us.